Albany Park’s Food Scene Represents its Immigrant Population, But Does it Indicate its Unity?

Olive oil sits in the middle of a thick swirl of grounded chickpeas. Warm naan bread dips into the hummus as harmoniously as the benju string instrument that plays the Persian music filling the room. An older white woman sits alone while a mother speaking a non-English language sits with her toddler-aged daughter. They eat the same bread influenced by a culture 6,499 miles away.

Across the street, Vicente Fernández’s ranchera voice and guitar entrances customers as they recline against tall wooden chairs with floral carvings. Crumbles of cheese spill out of a pork gordita, a small but thick tortilla shell. It’s difficult to keep the lettuce, meat, tomato and cheese all inside while taking a bite. Spanish fills the room, as mostly Latina or Mexican customers dip tortilla chips into a homemade pico de gallo.

Noon O Kabab and Taqueria San Juanito reflect the many cultures that make up Chicago’s Albany Park neighborhood. Yet, they also suggest that ethnic diversity in the population and restaurant cuisine does not translate to neighborhood integration and socializing.

Adrianna Bran, the owner of Taqueria San Juanito, says the restaurant sees 60% to 80% Mexican customers. On the other hand, the owner of Noon O Kabab, Mir Naghavi, does not necessarily see primarily Persian or Middle Eastern customers.

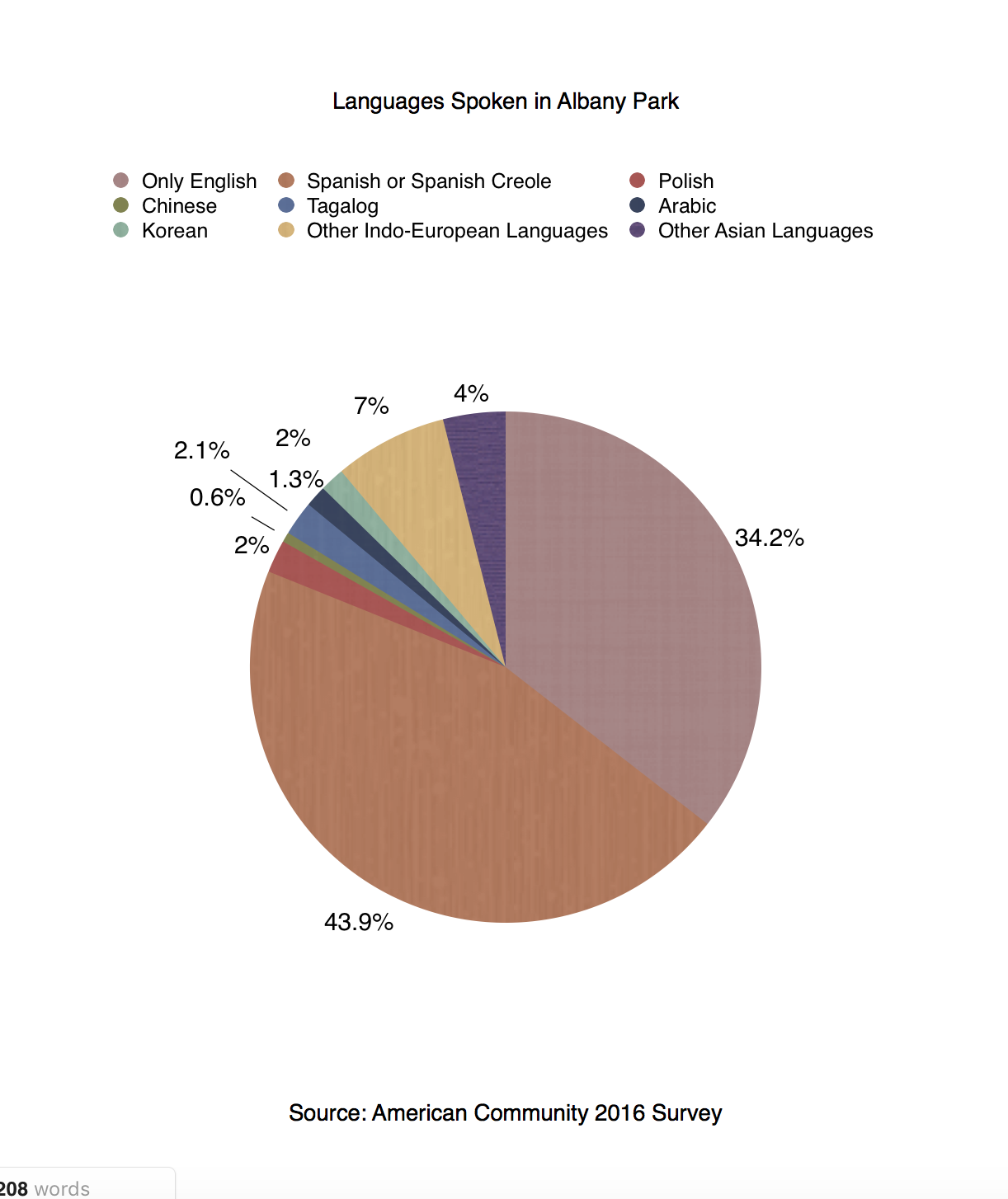

Both owners are immigrants, moving from Mexico and Persia respectively to Albany Park. Through their restaurants, they bring their homeland to Chicago. Immigrants from Guatemala, Palestine and Brazil have also opened up restaurants such as Tortuga’s Latin Kitchen, Salam Restaurant and Brazilian Bowl, using their culture from abroad as a business opportunity. Walking down North Kedzie Avenue, one reads awnings in Arabic, Spanish and occasionally Chinese.

Immigrants represent 27.5% of U.S. entrepreneurs and are twice as likely to start their own businesses, according to a study by Peter Vandor and Nikolaus Franke of the Vienna University of Economics and Business. Exposure to other cultures leads one to “encounter new products, services, customer preferences, and communication strategies, and this exposure may allow the transfer of knowledge about customer problems or solutions from one country to another,” Vandor and Franke write.

Their conclusion, that immigrants are more entrepreneurial because of cross-cultural understandings, is evident in the local restaurants of Albany Park. Although the restaurant owners might be experiencing a new lifestyle in America, they don’t always engage with neighbors from other countries who wok and live down the block.

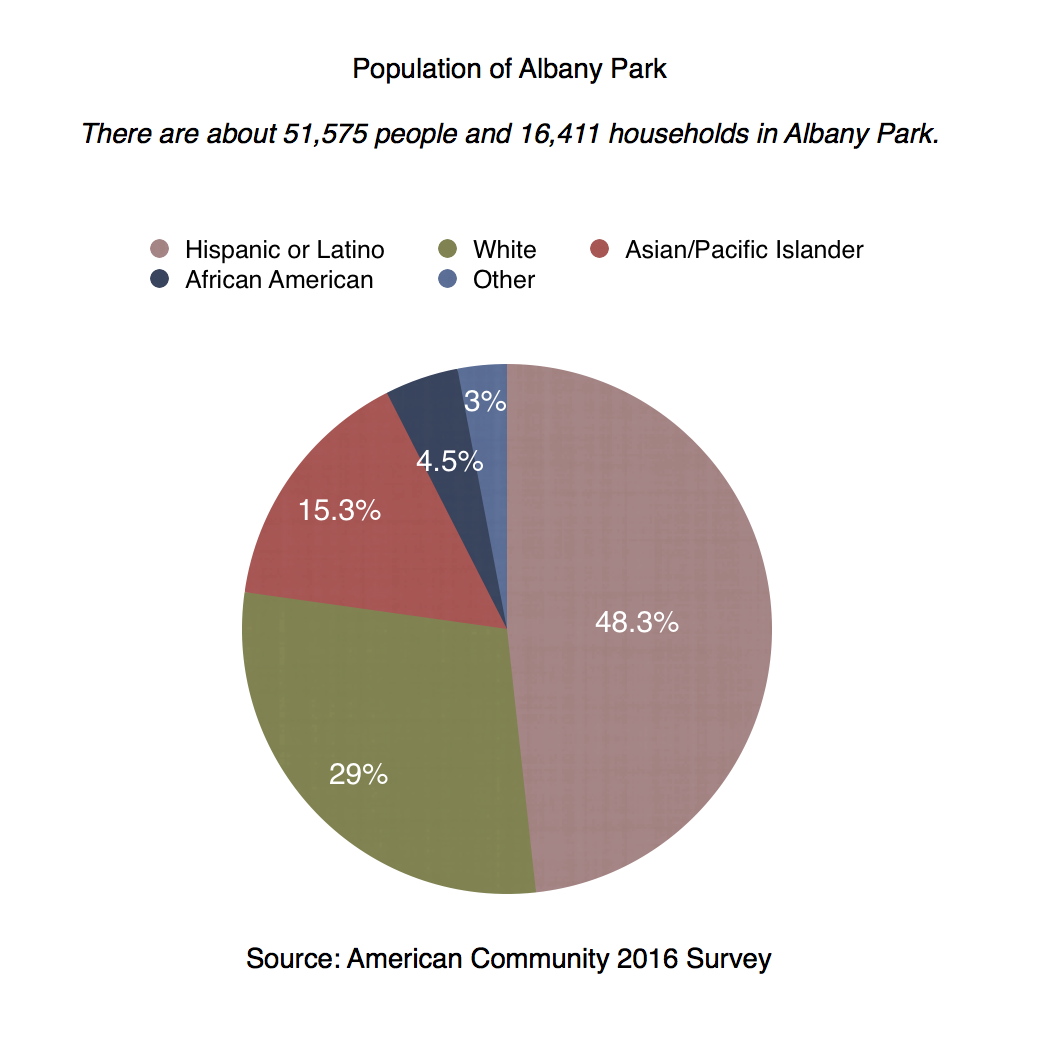

Around the 1880s Germans and Swedes founded Albany Park, says Thomas Applegate, the executive director at North River Commission. During the first World War, Russian Jews moved in, making it the center of Chicago Jewish life. In the 1960s, as Jews moved further north, immigrants from Korea took their place.

The echoes of the Korean population can be seen in the retirement homes and the ownership of many buildings, Applegate says. During these years, many people from the Middle East also moved in. Today, Albany Park does not see as many Middle Eastern residents but rather, many residents from Mexico, Central America and South America.

“We have a culture of welcoming and celebrating this idea of being a gateway for immigrants coming into Chicago,” Applegate says, “It’s something we all take pride in and contribute to. It’s something that needs to be maintained. It’s the way we talk about it: global roots, local hearts.”

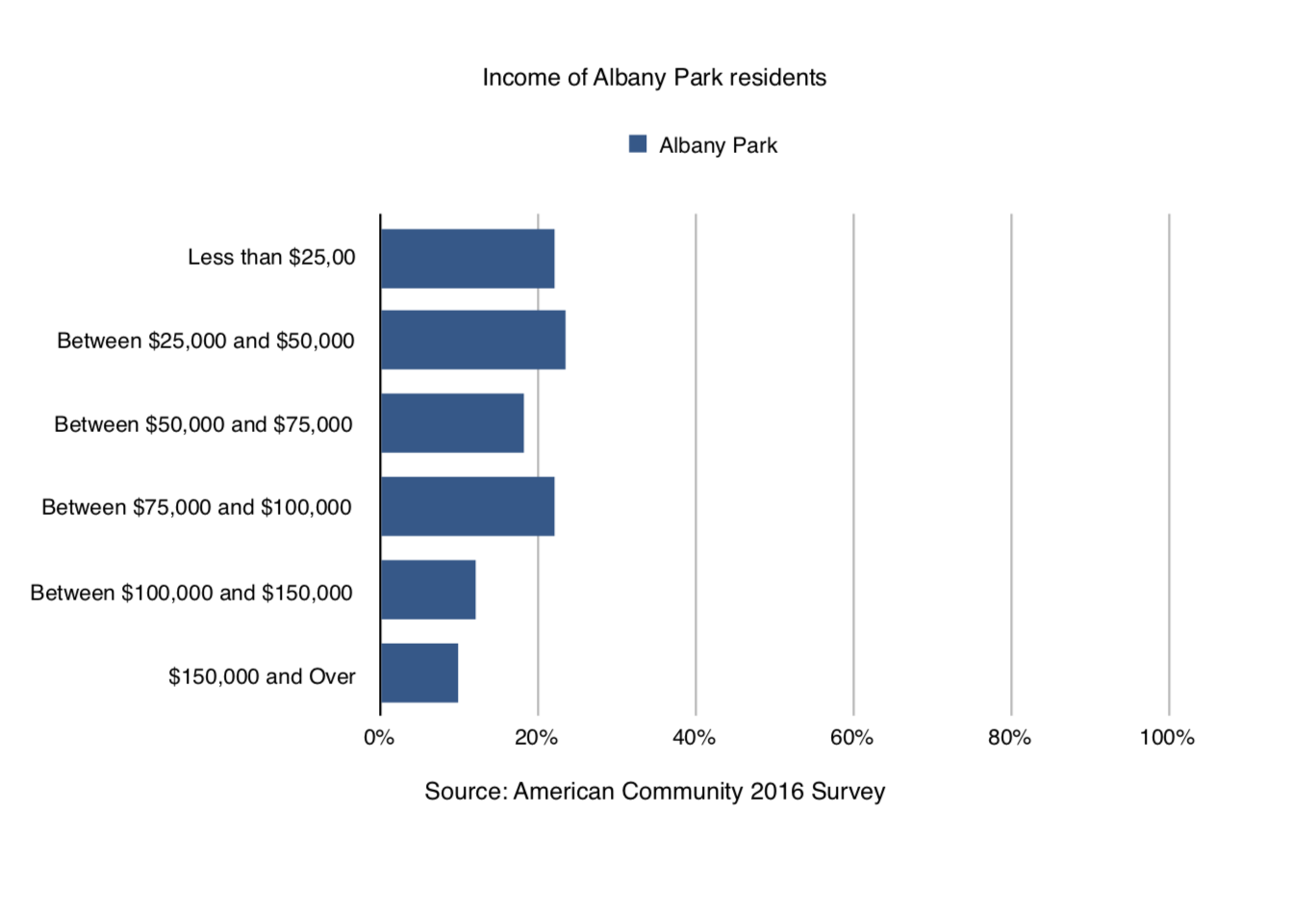

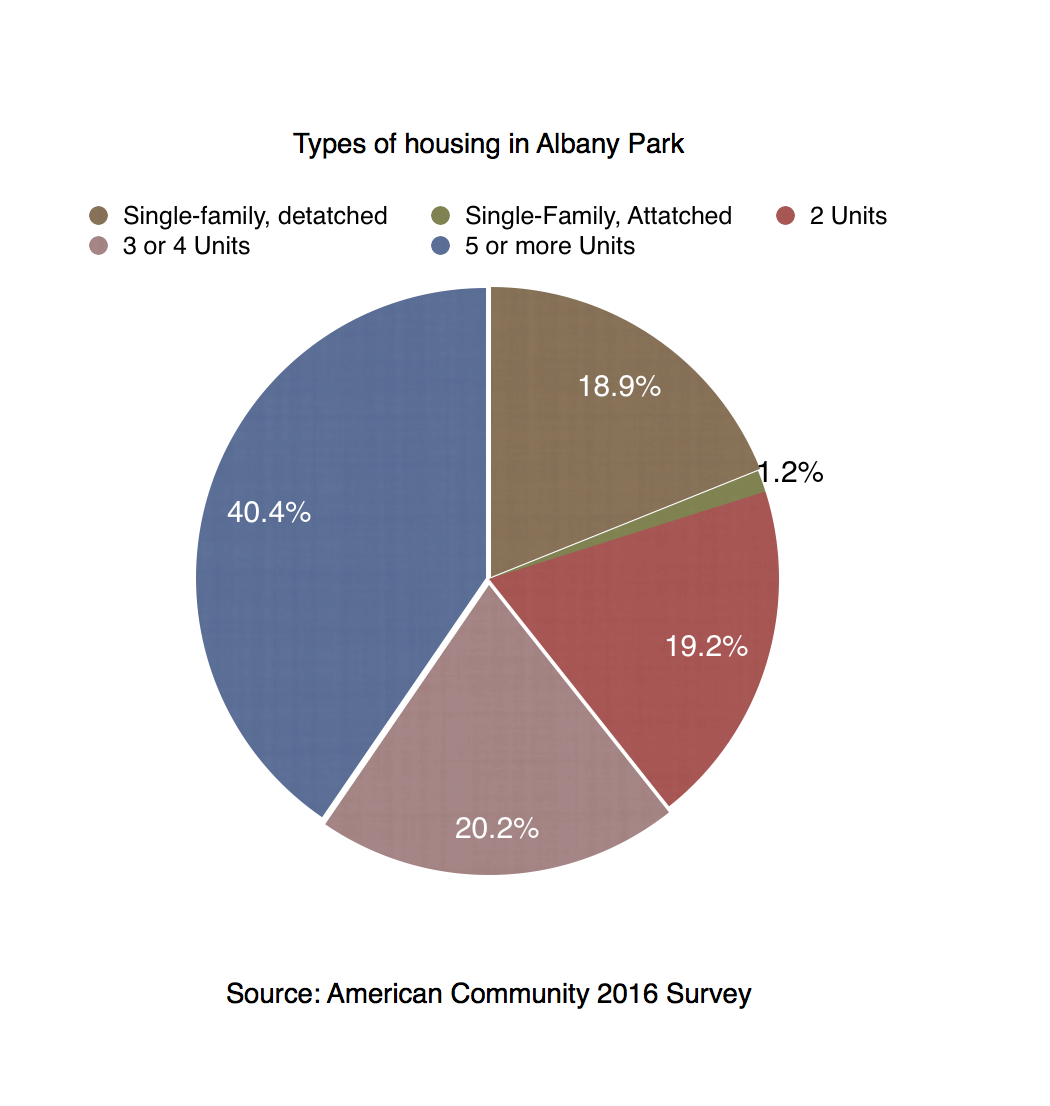

Applegate also attributes the popularity of Albany Park for immigrants to the housing affordability. Real estate agent Debra Dobbs says the price of condominiums ranges from $98,000 to $200,000, and the price of single-family houses varies from $270,000 to $965,000.

“All property types are doing quite well in terms of value appreciation,” Dobbs says. “You get much more for the money in Albany Park, which is what I think has contributed to it being what I would call a trending upward or popular neighborhood.”

Owner of Brazilian Bowl Tony Ferreira says diversity is the biggest difference between his two restaurant locations in Lakeview and Albany Park. But, he does not find that Albany Park necessarily has much dialogue between the many different immigrants, he says.

“I think it would be nice if we could meet more often and share our experiences and see what else we can do to bring business to Albany Park,” he says.

His restaurant replays Brazil carnival parade videos on two televisions while customers sit at steel countertops and black, wooden tables. Ferreira embodies this Brazilian culture meets modern American aesthetic as he wears his long hair tied back in a beachy, loose bun and speaks American-accented English.

Ferreira’s tall, lean stature match his description of Brazilian food as healthy and low in heavy spices and sauce. Most customers order the Brazilian Bowl, a protein of your choice served with rice, beans, vegetables, Brazilian pico de gallo, kale, cheese and Brazilian mushroom sauce. As versatile as he sees Brazilian food, he finds he works harder to gain Albany Park residents’ trust than in Lakeview. People in Albany Park are very loyal to the food from their home country, he says.

Noor Abraham, the manager of Salam Restaurant, fits Ferreira’s description of people in Albany Park since he mostly eats the cuisine from where he grew up, the Middle East. Seven years ago, he moved to Albany Park from Palestine. Sweat dripping down his forehead from the heat of the kitchen, he shrugs, saying that he does not venture to other restaurants in the area. He doesn’t feel a need to. However, Abraham and Salam still act as good neighbors, he says.

“If you need help, we help each other,” he says with a Middle-Eastern accent. “We have one new restaurant that opened last year and we helped him. He's a neighbor. I can’t say the name cause he’s closed, but we give him our experience.”

The restaurant sees Iranian, American and Mexican customers, Abraham says. During this May, Abraham and his family, who own the restaurant, were celebrating Ramadan. Out of respect, the customers did not eat in the restaurant much and ordered out, he says. Salam’s loyal customers highlight the neighborhood’s strong ties with its restaurants.

In the kitchen, Abraham works with Hamza Leo, who moved from Algeria three years ago. The two men share their respective country’s culture with each other, and while they are very different, have become best friends, Leo and Abraham say. They match each other in their “got taboleh?” uniform shirts and beards.

In comparison with the buff, to-the-point Abraham, Leo is quiet and struggles with English. Between work and university, Leo does not have much time to explore Albany Park, he says midst organizing the take-out order lists.

Similarly to Leo, Jairo Lopez, the owner of Tortuga’s Latin Kitchen, finds himself too busy with work to explore the rest of Albany Park. On the table, next to sheets of checks he is separating, his phone buzzes with a call for the second time. He tries to go to different restaurants but to learn about their managing styles.

Lopez describes his relationships with the people in Albany Park as “work relationships.” He met his close friends working at a bar downtown before opening Tortuga’s, he says.

In his red corps hat and legs crossed, he proudly says that in Albany Park he is the only restaurant to serve ceviche and have live music. Lopez started the restaurant in 2013 and serves a mix of Guatemalan, Mexican, Puerto Rican and Ecuadorian food. He says 80% of his customers are Latino.

“Behind the kitchens [of Albany Park], even if it’s Japanese food, Korean food or Middle Eastern food, you will find a Latino or Mexican working there,” he says. Lopez’s observation highlights the large Latino and Mexican population and suggests the cultural connectivity within the restaurants rather than between them.

For example, Bertin Hernandez moved from Mexico to Chicago in 1994 and works at the Middle Eastern bakery, Jaafer Bakery. Although he does not identify with the same heritage and culture, working at the bakery is not difficult, he says. Mostly Mexicans visit the shop, he says in Spanish since he doesn't speak much English.

At Taqueria San Juanito, Bran, like others, says she has no time to dine at other Albany Park restaurants. She arrived with her husband in 2000 and opened the restaurant in 2004. They brought wooden, floral-shaped carved chairs and vibrant landscape and portrait paintings from Mexico to bring authentic culture to their customers, she says.

Her head barely reaches the tall back of the wooden chairs, but her big smile fills the space with her spirit. She giggles when unable to fully convey her thoughts in English.

“I’m always here working in the restaurant,” one of her employees translates from Spanish. “I have no time to meet other people, but I wish I had more. I have not been given the opportunity.” Nevertheless, Bran will partner with her business neighbors to get an ingredient and sometimes refers a customer to another restaurant, she says.

“They communicate together. They have business friends and they exchange business information and networking,” says Jin Lee, the director of business planning and development and government relations for the Albany Park Community Center. “At the same time they are quite independently owned and operated.”

Because Albany Park restaurants struggle with language barriers and cultural differences in terms of how they run the kitchen and interact with customers, it can be challenging for people to try new cuisines in the area, Lee says. Chicago Eater editor Ashok Selvam agrees that customers don't try new places when they can’t communicate with the staff.

Though language may deter some customers, food quality in Albany Park is as good as downtown restaurants but not as expensive since pricing reflects rent, Selvam says. Unfortunately, the low prices cause some Chicagoans to see the quality as below standard, when in fact, the ingredients and labor are as good if not better than most downtown restaurants, he says.

Naghavi, the owner of Noon O Kabab, defies this substandard immigrant restaurant stereotype Selvam mentions. He prides himself on his international customers and kitchen, which he attributes to his Persian yet modern atmosphere. He offers a variety of kabobs and champions the mantra “feeding souls.” The Persian mosaics and music in the white table clothed, floor-to-ceiling windowed dining room give his Persian food a high-end style that defies the stereotypes Selvam says can be attributed with Albany Park’s restaurants. The casual wooden tables and counter ordering at the front of Noon O Kabob hint at the food’s affordability.

Naghavi moved to Chicago in 1978, and in 1997, his father opened up a storefront to sell jams. At first, Albany Park had many gangs. Naghavi worked with the North River Commissions to make the area safer. He says he even made friends with some of the gang members.

“The neighborhood needs a lot of help from the property owners,” he remarks. “There needs to be more beautification, like in the signs and awnings. The beautification not only bring the visual sensation to the picture but also bring an emotional essence to the community, so that itself creates positive memories and people would remember us and visit our community more often.”

Naghavi’s vision relies on the businesses working together to support each other and present themselves as a beautiful community, he says. Across the street, the owners and workers of Taqueria San Juanito may not be venturing to try naan and hummus, nor are its customers. But Naghavi sees a future that relies upon tasting other cultures so that Albany Park's workers and restaurants attain the prestige they deserve.